A couple of days ago I was driving through town and I saw an A-board outside a little café that said ‘coffee, bratwurst and vinyl’. Which I think most people would agree is a somewhat strange combination.

Do you think that was in the original business plan? Or it evolved this way over time perhaps due to an incorrect shipment of German sausage that suddenly proved popular, or a large inherited music collection from a recently deceased relative that needed storing somewhere. I remember the café used to be called something else (one of those unoriginal coffee houses that dared to admit it hadn’t even considered pork-based offerings nestled in-between 45s) and I had assumed it changed hands, but maybe it was some epiphany that prompted a new direction. I can picture them sat there for days:

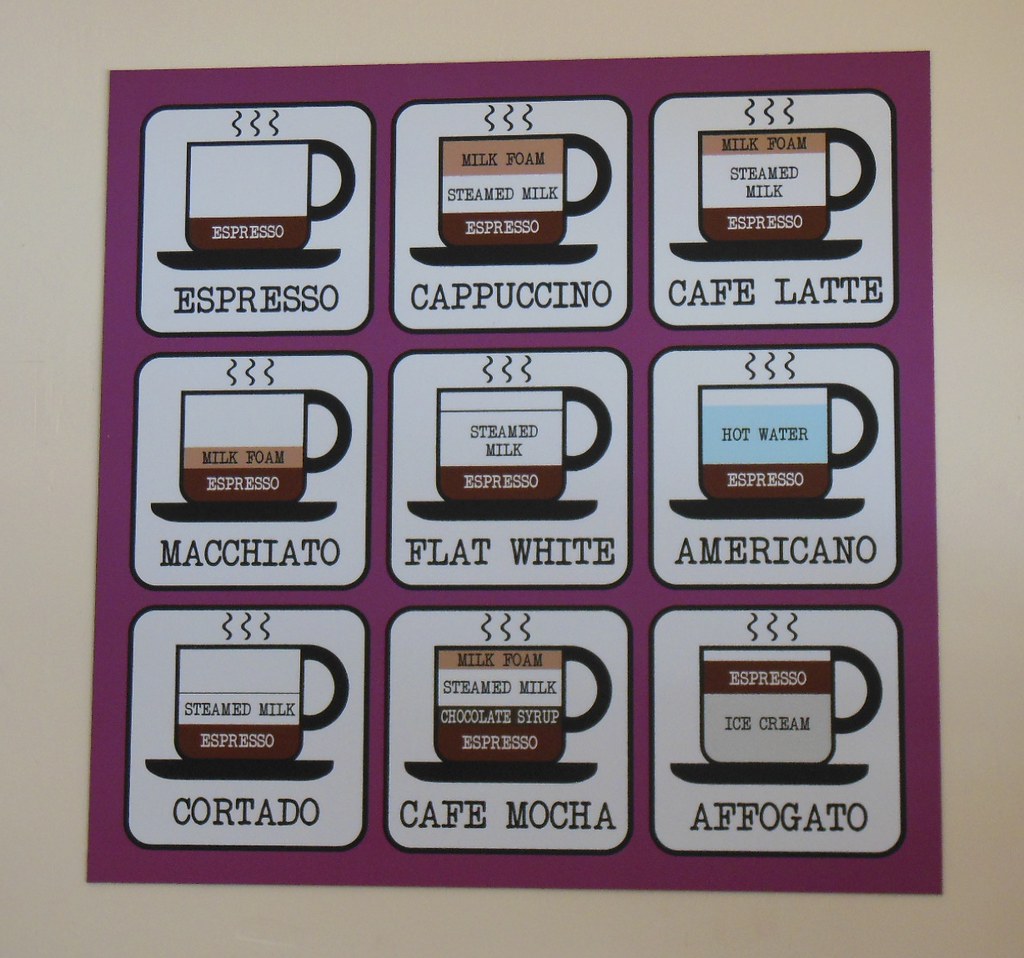

“Caffeine alone, its just no working. We’re only as successful as all the other coffee places in this town. We need to add two more things.”

“How about tea, mince and bowling?”

“No, no, no.”

“Latte, casserole and cartography?”

“It’s good, but it still doesn’t feel right.”

“Hot chocolate, bagels and ammunition?”

I imagine it going on and on like that before finally landing on the sacred idea, embracing as they did, tears streaming down their cheeks and looking toward the blessed sky with relief.

Well, I suppose they say the best things come in threes. And then there’s the rule that all good speeches have. Most classic orators will use three examples, or three key principals to express their argument. It’s supposed to be more effective. It speaks to the human brain, the same way we like our stories to have a beginning, a middle and an end. Why Goldilocks had to meet three bears instead of just one, which let’s face it is usually unlucky enough.

“Mocha, satsumas and dog training?”

Some stories, although in literal terms must have a beginning, a middle and an end, only do so in the sense of time it takes to read them. Our bookmark is placed half-way through the book so we must be in the middle, but the story itself doesn’t necessarily read like that. There’s no definite sense of an ending – that’s a Barnes book, isn’t it? I mean, it ends, the words stop and we’re suddenly accidentally reading the acknowledgements, but it doesn’t feel finished.

“Cappuccino, kale and plastic surgery?”

I remember doing a module back in the day on ‘modern’ short stories, most of them post-war. I appreciated what they were doing from an intellectual point of view, and in a way, they probably reflected a collective feeling for those of that era, who felt so turned upside down by war. All that they hoped would be different afterwards didn’t necessarily materialise, in addition to processing the ongoing traumatic aftermath. But I also imagine people of that time didn’t read books to stay feeling how they already felt, but perhaps in the hope it would make them feel better. Or at least different.

“Cortado, cheese and therapy?”

I guess you could come back to a similar argument about satire and catharsis. Tapping out a sketch that really lays into a corrupt government is fantastic for the soul (that nice, neat ending feeling), but does it dampen your ardour to actually do something about it? But what can we actually do about it if it’s been voted in democratically? We can protest certain laws and sign petitions but that doesn’t often instigate a lot of change. At least it’s a way of sharing our collective outrage, and sometimes in a way we can’t do with just a speech, even with the rule of three included.

“Macchiato, cereal and hypnosis?”

But what about how the politicians or those in the public eye feel about the satire aimed at them? Many see it in a positive light. After all, no publicity is bad publicity. Many will openly say they find it funny so that others appreciate them for being able to take a joke at their own expense, which can serve to increase their popularity. And they might genuinely find it funny. Or in private sneer and snarl and the indignation. As only the writer, we don’t get to know. And that’s certainly not to say that satirists are saints shedding light on the less than chivalrous behaviour of our betters, as sometimes they can be downright cruel. But that’s because they didn’t follow the golden rule: APU – ‘always punch up’. Otherwise, its not satire, its bullying.

“Espresso, noodles and reiki?”

The other golden rule for a classic satirical sketch is you’ve got to end on a strong punchline, especially for live shows. The audience needs to feel that ending and the performers to have earned their applause. Don’t leave your comrades out there with no ammo, give them the means to punch up.

And this is what I need (well want, but it feels like a need) from stories. The ending doesn’t have to be a happy one, but it should feel like an ending. You don’t need to tie up every loose end or resolve every tension, but as a reader I appreciate at least a clue as to what the author hoped I’d get out of it. Just a hint will do, I don’t mind doing the work. In fact it’s often more satisfying that way, but don’t leave me hanging without even a small thread to tug at. Maybe this makes me ‘vanilla’, scared of experimentation, but the truth is writers have done lots of experimenting over the years and there’s a reason why most bestsellers follow the old ways. Because we don’t get it in real life, sometimes tragically so.

So with that in mind… anyone for a flat white, a taco and some glass blowing?